Creamerie is the new darkly funny dystopian comedy streaming on TVNZ 2, and was created with the support of New Zealand On Air. Written by Roseanne Liang, it stars Ally Xue, J.J. Fong and Perlina Lau – a trio you may recognise from Flat 3 and Friday Night Bites. We captioned and audio described Creamerie, and our amazing community of viewers who’ve watched with these services submitted questions for our interview with co-creator and co-star, Perlina Lau!

Spoiler alert and content warning: This interview discusses content from Creamerie Season 1, Episode 5 (aired on TVNZ 2, Monday 17th May).

Kia ora, Perlina! Let’s talk about Pip as a character. What made you want to create and play her?

We wanted to make sure that we had three really different, grounded 3D characters. Jaime’s a very grounded, very real character, who is still in grief, trying to get over everything that happened eight years ago and everything she lost. Alex is quite badass, she’s got that staunch character; but she’s grieving too, in her own way. If you have these characters who are grieving the past, you also need one who looks to the future, and that’s Pip. She’s looking ahead, looking to this new world, and trying to find the hope in it. She wants to see the good things, she wants to believe that Lane and her cronies have got the right intentions, and that they will all be looked after. Pip is naive, and she’s the comedic one; but she also serves as the character who is trying to find the good in the new world.

How close are the three protagonists to the three of you in reality?

I think that growing up I was quite a goody-good… So perhaps that element of Pip’s character is true for me; and when you blow that up to an adult – I think you can have kids that are goody-goods; but adults are a different breed! It’s quite funny. In general though, I would say that we are actually quite different from our characters in this show. I think viewers will find something in every character that’s relatable, and I suppose that’s what we mean when we say 3D, is that people are so complex. Pip is annoying and naive, but she also says what people are thinking and don’t want to say, and she can feel guilt and remorse. That’s what we wanted – to build three protagonists that a viewer could empathise with.

Do you think Pip is ultimately a victim or an accomplice? Ie. is she truly a product of the system, or is she just a weak people-pleaser?

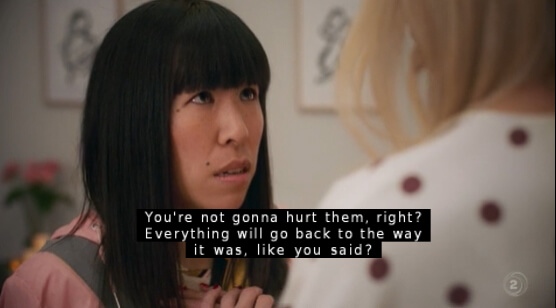

I would almost call it willful blindness. She knows, deep down, that something is off, but she has this desperation to see it differently: wanting to be in the Wellness committee, actively ignoring all the red flags, and ultimately betraying her friends… I think she wants to believe she’s a victim to a degree, but I think with her character and where she’s come from, she’s just so desperate to believe that this new world will work for her, and she convinces herself that this is the case. I think that’s something that we’ve all done in life.

Creamerie is set in the beautiful, fictional ‘Hiro Valley’, a lush dairy farm in rural Aotearoa. Are there any ideas of provincial or urban New Zealand that you think are central to the show?

The subject matter of the show is so big. This huge, catastrophic event has happened, and so to contrast to that, we’ve zoomed into this tiny town. It’s based on (our idea of!) rural New Zealand, and we chose to set it on a dairy farm because dairy is such a huge important export for New Zealand. It’s also representative of a place where so many people have grown up and can relate to, and such a beautiful backdrop to show off our country. We liked the idea of zooming in on a small place, and really telling the story of these few characters.

Is it a commentary on New Zealand, for you, in any way? Or on potential contemporary dystopia?

I think it’s a combination of both. When you’re creating a dystopian world, in some ways, there’s so much freedom and you can do anything. Our whole team are Kiwis. The writers are Kiwi, the cast are Kiwi. We knew that the tone, comedy and the humour would be distinctly Kiwi, and it’s set in a location that would be very recognisable to New Zealanders. However, in terms of the themes and messages of the show, it’s more universal. We were looking at what’s going on around the world, and the extreme polarisation of views and beliefs. With our show, we’re trying to say there must be yin and yang, there must be a balance. We can’t exist in extremes, we must be able to understand the other side of the story, and that’s the only way you can achieve anything. You can see that everywhere in the world.

What were the challenges of the role?

This role was really exciting to me, but also really challenging. We had been playing our Flat 3 characters for so long. They’re very actively funny, and the web series has always been a bit of a wink to the audience. This role was completely different. It’s a dramatic role that takes place in this dystopic world. It’s high stakes, it’s stressful, and my character is confused a lot of the time!

In terms of challenging scenes, I was so apprehensive about the dinner party scene, in Episode 5. It’s a really awful situation, and something that you don’t see on screen. It’s hardly, if ever, portrayed that way round. I wanted to make sure that I gave gravity to the situation, and that we were portraying the seriousness of the incredibly heavy subject matter. On top of that, we wanted to make sure that everyone was comfortable, and felt safe. It was a scene where we relied heavily on Jennifer Ward-Lealand for her intimacy co-ordination, so that was central and paramount to that scene. It’s so physical, in so many ways, and so it meant choreographing every single move. There are so many people sitting around that table, firstly, and then there are so many physical interactions between the characters. There’s pushing, shoving, climbing on the table. It’s so active. It’s literally intimate, and awful for everyone on a different level.

How was filming in a pandemic?

Bizarre, really bizarre. We had two days to shoot that dinner party scene, and after the first day of shooting, we went into the second lockdown overnight. Everyone that night had to pack up, we had to get everyone out. There was fresh seafood, there were flowers, there was meat, it was full on! We were then sitting on our hands for two weeks, and we came back to filming and everything had changed. Everyone was social distancing, the food was served differently, we had to drink plastic bottles of water, we couldn’t touch anything. We were all talking through our masks, so it’s hard to hear. The flow and the protocol were totally different. It was a reminder, I think, that we were so lucky that we were able to film at all. By the time we were shooting, the pandemic had been around for about six months, so we were well into this new world. Filming a show like that, in the time that we did it, was just so surreal.

What’s your response to the criticism that the virus-related subject matter is in poor taste – that it’s too close to reality?

We pitched this in 2018, and came up with the concept two years before the pandemic unfolded, and even when we got funding, it was two years before we would shoot. By the time we were ready to shoot, half of the work had been done, and that was when the pandemic hit. We had to really take stock and think. We closely monitored what was happening, looked closely at our storyline to ensure it wasn’t imitating real life, but I think at the same time, when there are things happening in the real world, people don’t mind seeing it on screen. There’s something about art and life imitating each other that people get some sort of relief from. It’s almost like they look for answers if they don’t feel like they’re getting it. When lockdowns began, everyone started streaming Contagion – the viewing numbers went through the roof! There can be a sort of fascination in art that’s subject matter is so close to home. I felt very similarly when watching The Handmaid’s Tale, when I saw aspects from it playing out in reality, in the form of laws and policies in the US.

To a degree, there’s a lot of grief in our show, and that’s something that people can understand. In some ways, a dystopian setting can be a great way to help people to process – it’s close enough to reality that you can recognise it; but far enough away to give you the distance to see the message in there. Comedy, too, especially this very silly form of comedy, can be a relief, so it’s there for people to make their own decision about watching.