On 9th February 2022, Kathryn Ryan spoke with Wendy Youens, our Chief Executive (CE), and John Mulka, CE of Blind Low Vision NZ on RNZ’s Nine to Noon. The interview can be accessed on RNZ’s platform here, and the transcript of the interview is below.

Katherine Ryan: People who are deaf, blind or have low vision are currently missing out on being able to fully access one of life’s simple pleasures, watching TV. Currently, New Zealand on Air funds closed captions and audio description services, but it doesn’t cover all scheduled programming. There’s no legislation requiring a minimum amount of captioning or audio description, putting New Zealand out of step with other OECD countries. Over a million New Zealanders are either deaf or hard-of-hearing, or blind or low-vision. It’s hoped that better access to media will be captured by the proposed accessibility legislation, which was unveiled by the government in October, alongside a new Ministry for Disabled People. Disability advocates warn the new legislation must include provisions for accessing information, communications and technology, and if lawmakers don’t get it right from the outset, it could take decades to undo the damage. John Mulka is chief executive of Blind Low Vision New Zealand. Kia ora, John.

John Mulka: Good morning.

Also with us is Wendy Youens, who’s chief executive of Able, the country’s leading provider of media access services, including captioning, audio description and subtitling. Kia ora, Wendy.

Wendy Youens: Mōrena.

So can you explain, please, what Able provides – the captions, the audio description? Just give people an overview of what’s possible.

Youens: So Able is a not-for-profit organisation. We’re fully funded by New Zealand to provide closed captioning and audio description. Closed captioning is provided for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community, and it’s a transcription of the programme’s audio; it’s displayed like subtitles. Audio description is a service for people who are blind or have low vision and provides an alternate audio track that describes the on-screen action. Able provides services for TVNZ, Discovery and Prime. And as you said earlier, there’s a wide range of services available, but it doesn’t cover everything in the television schedule.

So for people with low vision, you will have a voice describing what’s happening where there’s no conversation, visually describing what’s happening in the scene, correct?

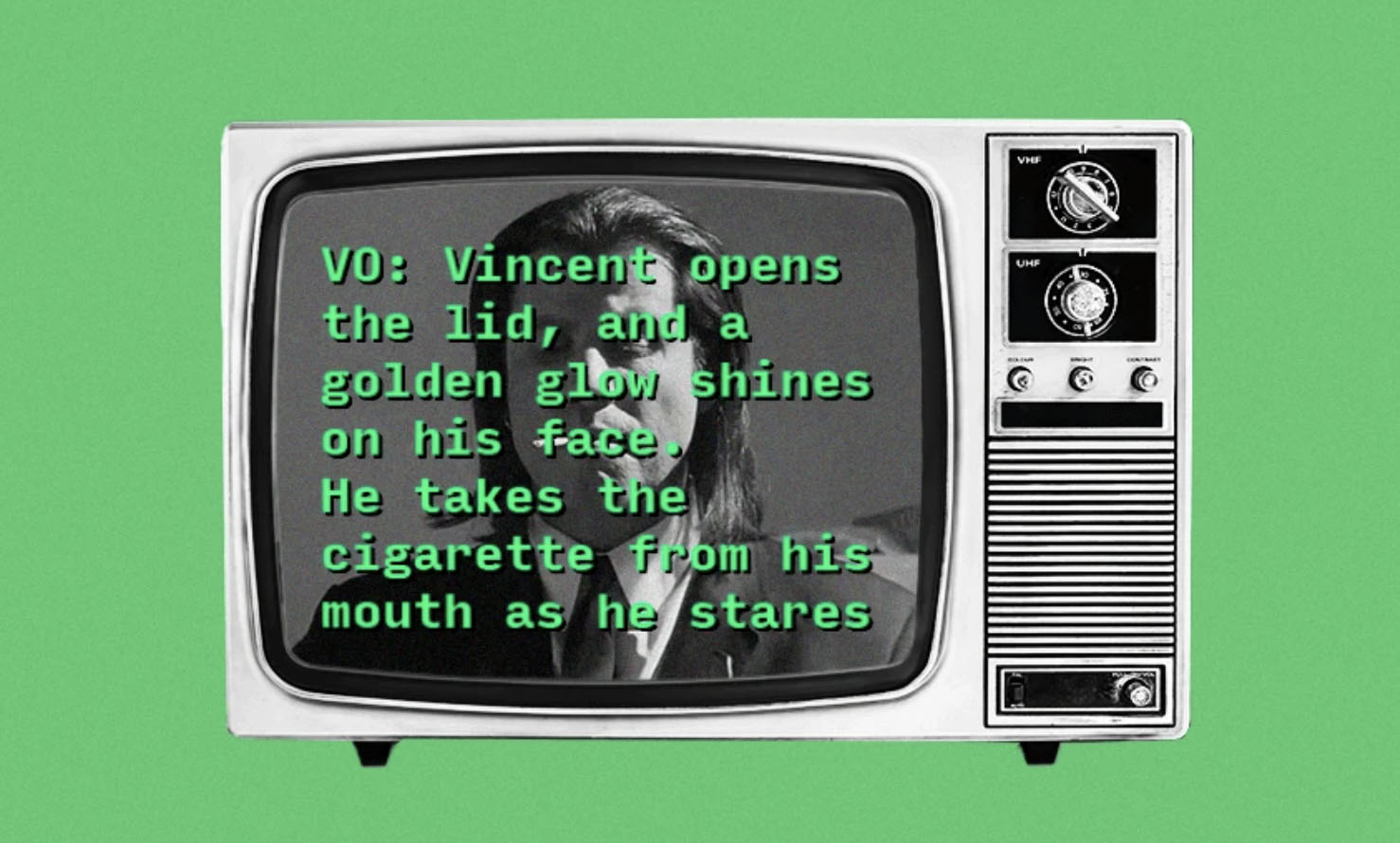

Youens: That’s exactly right. So the audio descriptions are in between the dialogue and important audio, and they describe exactly what is happening on the screen so that a person who was blind or has low vision can follow along with what’s happening and understand what’s happening in the show.

When it comes to each – to captioning for those with hearing loss or the audio description for those with low vision – what’s involved? Can some of it be done by machine learning? Or is it quite labour intensive? Does it require people, you know, doing the inputting or making the audio recordings?

Youens: So the process that we use for captioning is basically through using a lot of really clever technology with a human touch. So we have a team of highly trained captioners who use technology like artificial-intelligence voice-recognition technology. So there’s not a lot of manual input involved; there are a lot of automated processes. But you still do need a human involved at some point in the process to make sure that the technology is doing the right thing, especially when dealing with the tricky New Zealand accent.

Yeah, machines can do odd things, but they can do some of the hard graft at the start, right?

Youens: Exactly. It really speeds up the process for us to use technology, so we try to use it to our advantage.

When it comes to audio description, is that a human being doing most of the work?

Youens: Yes, audio description is still a very human-based workflow, so we have trained audio describers watch the programme; they write an audio description script, and then they record that script. There’s certainly some clever technology that helps us, but it really does require a human to interpret what’s happening on screen and decide how to describe that in a succinct way that fits in the gaps in the programme’s audio.

When we look at what’s available, captioning is currently available on most free-to-air channels. I’m looking at TVNZ 1 and 2, Duke, TVNZ OnDemand, Three, Bravo, ThreeNow and Prime. Well, actually, that’s kind of the news and information TV channels, isn’t it? Then audio description is on TVNZ 1, 2 and Duke but not available on TVNZ OnDemand, Three, Bravo, ThreeNow or Prime. Let’s talk about live captioning. What’s different about it? And how available is it?

Youens: Yeah, so live captioning is currently available on TVNZ channels, so TVNZ 1, 2 and Duke, and it’s also available on Prime for some programming. So at the moment, we’re providing live captioning for some of the Winter Olympics coverage that’s on Prime, which is a great challenge for our captioning team. And live captioning is provided, again, using technology with a human touch. Our captioners are using as much information as they can to prepare the captions in advance, so accessing newsroom scripts and preparing the captions in advance so that they are as correct as possible. But of course, particularly with live sport or live news, there are lots of elements that you can’t prepare in advance. So the captioners are using live respeaking technology. They’re listening to the audio, and they’re respeaking what they’re hearing into special software that converts it into captions and broadcasts in real-time. So it’s quite an intensive process.

It is. It’s very similar to the real-time translations that diplomats benefit from with skilled translators next to them, and then it’s converted into text. So if the live captioning is most relevant, I guess, during breaking news, COVID updates… Although we are seeing an increasing use of Sign and actual signing happening, say, in the likes of some of the official government media conferences for those who can sign. But it’s things like election nights, for example, things where real-time drama is happening –is it much more limited, the availability of live captioning in New Zealand?

Youens: So we do provide wide coverage of live captioning on TVNZ channels, but we don’t provide that kind of service for other channels like Discovery’s Three or for news on Prime. So what we have at the moment really is a lack of choice for viewers. So Deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers can watch most live content captured on TVNZ. They can watch, for instance, election-night coverage or live debates, breaking news, COVID press conferences. But they can only choose to watch that on TVNZ channels. They can’t watch, for instance, Three’s news coverage. So they’re not getting that choice, because currently, Three doesn’t have any technology to broadcast live captions, so we’re not able to provide services to them.

So is this not about a New Zealand On Air funding issue. The actual companies doing the broadcasting need a certain amount of technology.

Youens: That’s partly right. So the situation we have at the moment is New Zealand On Air funds Able to provide the services to broadcasters. We then provide the broadcasters with those services at no cost, and the broadcaster’s responsibility is to have the technology to broadcast those services and to make sure that they get to air and that viewers can access the services. But the situation we have in New Zealand is that broadcasters don’t have any obligations to actually make their platforms accessible and have that technology in place. So it’s up to each individual broadcaster how much they want to invest in that technology.

Which is where this legislation comes into play potentially, right?

Youens: Potentially – that’s absolutely right.

We have seen a significant increase over the last six or seven years in the amount of captioning in particular. There’s been an increase also in audio description, but it’s coming off a low base, yeah?

Youens: Yeah, that’s right. We’ve started from a low base. Certainly, over the last decade, the services have grown massively. We did have a really significant funding boost from New Zealand On Air two years ago, so there was an increased fund available for public media organisations, and some of that money went to Able. We had our funding almost doubled. So we’ve been going through an expansion phase, and we’ve been growing all of our services, but we’re still grappling with these inconsistent platforms. We can’t provide services to a broadcaster that can’t actually broadcast them. So we’re able to increase and do more in the places we’re already providing these services, but we would just love the broadcasters to improve their own platforms and technology so that viewers have a really consistent service across all of the main free-to-air channels.

Wendy, just before we come to John, there’s a fairly obvious elephant in the room here, which is that we’re also watching live free-to-air broadcasting decline as a proportion of the total viewing that people are doing. So more streaming services – for example, various sort of paid TV services and, of course, the on-Demand services – being able to go back and go through a library and watch what you want of potentially recently broadcast material. So with that shift, what’s the possibility and what’s the challenge?

Youens: Yeah, so we are definitely seeing that shift, and we know that our viewers who are accessing captions and audio description want access to those services online as well. TVNZ OnDemand has captions available online. It doesn’t have any capability to provide audio description, which again, it’s just inconsistent for viewers. They have to watch it on broadcast TV; they can’t catch up later. So we really want broadcasters to invest in the online platforms so that the services we’re funded for are getting the most amount of airtime in the New Zealand audience – getting the best bang for its buck, really. But certainly, the introduction of Netflix and other overseas-based platforms has been great for people with accessibility needs in New Zealand, because those platforms are fully accessible due to legislation in the country where it comes from.

OK, so fully accessible in that they’re available in the content. But again, is there some kind of technology gap in order for New Zealanders to be able to access some of that? Or can they access on Netflix? Can they access these full services?

Youens: On Netflix, they have 100% captioning. So every show you look at on Netflix has captions available, and there’s quite a wide percentage of audio description available, and obviously, they also have subtitles and lots of other languages. So there are lots of different accessibility services, and New Zealanders can absolutely access those things, which has been fantastic. And I think it’s actually seen an increased demand for services here, because people are saying that it’s possible, that it’s available and they want that same access for New Zealand content and for the free-to-air content that we’re all watching on broadcast TV.

Just a last question to you – what is the capacity of your industry, which is fairly specialised, to cope with what a legislative change might introduce? Will it suddenly double, triple, quadruple your workload?

Youens: Yeah, possibly. I think that it would probably introduce competition, so there would be other players in the market. There are lots of international companies that provide the same services as us. And particularly if broadcasters were required by their legislation to actually pay for the services that we’re providing, it would certainly introduce a completely different framework and way of working and moving away from that funded, not-for-profit situation that we have now, which has many benefits but, as we’ve been discussing, doesn’t provide the consistency that viewers are wanting and the wide breadth of services that viewers are demanding.

Stay with us, Wendy. John Mulka, can I bring you in now, please? Chief executive of Blind Low Vision New Zealand. Wendy’s given us a good overview of what’s possible. Could you pick up, please, on what your members and, indeed, the Access Alliance are looking for?

Mulka: Well, thank you for the opportunity. Wendy, I just want to commend Able for what they do do for New Zealanders currently. I think they do a phenomenal service; NZ On Air for their support of Able. But the reality is we have a gap, and we have a significant gap in this country. And that’s what Wendy spoke to – that not all programming is available in alternative formats and accessible formats. And that’s where the Access Alliance and our Access Matter campaign comes in, with the accessibility legislation that the government committed itself to in October of last year. With that, we believe that we have an opportunity that everybody in New Zealand who should have access to the same programming… ‘As a sighted person and, you know, fully able-bodied, I can watch television any show I wish,’ and our position on behalf of the Access Alliance is that should apply to every New Zealander. So there is legislation in other countries that have achieved this. As Wendy alluded to, the example would be Netflix. Obviously, in the country where it’s produced, they have accessibility laws that say that the content must come in accessible formats, and that’s what we’re striving for here in New Zealand. Again, I want to commend the efforts of Able. I think they do a phenomenal service. We just want it to be across the board and available for everybody when they choose to watch television in this country.

Do you believe this legislation, which is very nascent at the moment, not a lot of detail – this is the disability legislation the government has foreshadowed but is still drafting – that it will be absolutely key to the shift?

Mulka: Absolutely. I can’t emphasise that enough, and the reason why I say that is it starts with legislation, but it also starts with standards, and standards with teeth in them – in other words, accountabilities. It’s one thing to write a legislation on a piece of paper and produce it, but it’s another thing to enforce it and hold people accountable to it. And that’s going to be the key. Your opening comments, which I totally agree with – if we don’t get this right coming out of the gate in terms of the legislation and what it states must be done along with standards, then we will probably spend decades undoing the damage. So it’s very key at the outset that we establish it, we’re firm with it and it’s clear on what needs to be included in the legislation when it comes to accessibility needs.

What conversations or discussions have you had with governments so far?

Mulka: Very preliminary discussions. Obviously, you know, the process, it’s been a journey. Pobably over the last five years, in particular in the last couple of years, it’s really come to fruition with the announcement by government. I believe we still have a lot of work in terms of the actual legislation that’s to be presented in Parliament and ultimately approved. There’s a lot of work to be done – I guess, is what I would summarise – between now and then. Your question around the conversations with government – I believe they’ve been very favourable and appropriate, and we’re all trying to work to the end goal, which is a very robust, all-inclusive accessibility legislation for this country.

North America and the UK, I think, have minimum standards; some, at least, 100% requirement – 100% of content to be captioned and to have audio description. I’m presuming this is content produced at home. As we’ve said, if you’re buying in some international content, you may have the benefit of it being already embedded. But when we’re talking 10%, is it locally produced content?

Mulka: Yes, it’s my understanding. It’s anything that’s produced in the country that has that legislation. Locally produced content has automatically come out as fully accessible.

I know this legislation goes much wider, and we’ll talk about it, John. We’re talking about the viewing here, viewing first, and in the broadcast form but also in online form through streaming. Websites must be another really big issue, right? What proportion of websites… What is possible by means of accessibility with websites, by the way? Is there technology that can actually make this much simpler than it sounds? What might you be looking for in an area like website accessibility?

Mulka: Well, right now, unfortunately, 90% of the websites in this country are not accessible. And in the digital world that we live in, whether you go online to order your groceries, you want to book a bach for a weekend, you want a, you know, flight – whatever it might be – those certain websites are accessible. But as I said, 90% of them in this country currently are non-accessible. And it does involve some programming on the outset. We encourage organisations and companies who are developing a website to consider that from the outset. There is a little bit of extra work involved in it, but it’s not insurmountable or monumental that it would defer you from doing it. So it’s the old adage – build it at the outset in the proper format, and then people can enjoy it. So sad to share that fact with you, and again, there’s another example of a lot of work that we have to do.

John, government could and should lead the way on this, surely, because I’ve already mentioned a million of us with low vision or hearing impairment, to some degree. We’ve got an ageing population, so we know that percentage is going to grow significantly. The onus is on government, isn’t it, to provide its taxpayer-funded services in a way that everyone can access?

Mulka: Yeah, it does start with government, for sure. I’ll agree with your statement. The onus is on government, and I think the onus is on all of us as a society, as businesses, as charitable organisations and citizens of this country. But it does start with the government and the onus, and we have the opportunity now. The government has made the commitment that they want to have accessibility legislation in this country, and I go back to my comments; I think that’s the first thing, and we should celebrate the fact that our government is of the knowledge that now the next step is the legislation in the standards and the enforcement of those standards.

John, thank you very much. John Mulka of Blind Low Vision New Zealand. Wendy, if you’re still with us, just as an aside – unrelated but an additional bonus I get to all this– there has been some research done into what happens with younger children watching television when there are captions on screen.

Youens: Yes, there has been some really interesting research about literacy. So using captions can double the chances of a child becoming good at reading. And it’s proven that reading subtitles helps children with word recognition and letter recognition. So actually, as you know, there are really wide uses for captioning, which I think is just fantastic for accessibility overall.

Best to read of course, when you’re on someone’s knee and talking about the text with them, but if you are going to be having some child time in front of television, it’s interesting that there’s an added bonus to text being involved.

Youens: Yeah, absolutely. And you know, it makes sense to just put the captions on; they’re benefitting everyone. And also, it means you don’t need to have the volume as loud, which is great.

Wendy, thank you. Thanks very much, Wendy Youens and John Mulka.